İlim ve Medeniyet

Yeni Nesil Sosyal Bilimler Platformu

Relations between Iran and Armenia have continued since ancient times. These relations have many dimensions, including cultural, political, and commercial aspects. Historically, the name “Armenian” was first mentioned in Persian sources. The language that influenced Armenian the most has been Persian. During the Achaemenid period, Armenians—alongside Persians and Medes—held significant positions in the army. The first Armenian churches were built on Iranian territory, and during the reign of Shah Abbas, Armenians were deported into the interior of Iran through the “Great Deportation.” Although they mostly lived under favorable conditions, there were also periods when their properties were confiscated. Today, Armenians are considered among the happiest religious minorities in Iran. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia’s main patrons became Russia and Iran. While Iran benefited from the Armenians’ lobbying power, Armenians in turn benefited from Iran’s military and geopolitical strength.

During the Achaemenid and Parthian periods, Armenians were more in a position of being influenced. In these eras, a significant portion of the names used by Armenians were derived from the names of Achaemenid and Arsacid (Parthian) kings. Before accepting Christianity, Armenians shared a religion similar to that of the Iranians. Armenians learned much of their religious terminology through Persian. Various sources state that the relationship between the two peoples spans approximately 2,800 years, or even earlier. The names of Armenian and Iranian gods also display considerable similarity.

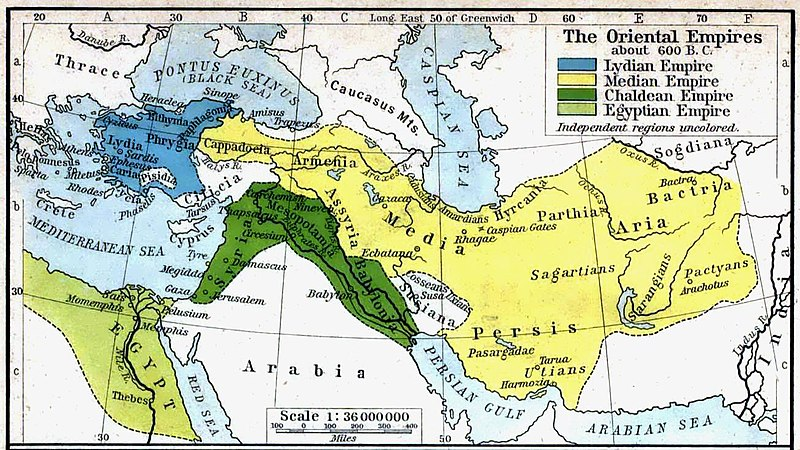

Iranians migrated from Central Asia to the Iranian Plateau in the second millennium BCE. Their names began to appear in written sources in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE. They entered the stage of history with the Medes (700–500 BCE); however, the Medes did not leave behind many written works. During the Median period, there was significant interaction between Armenian and Persian, and Armenian borrowed many words from Persian. This era was a time when peoples gradually began to emerge and take shape. It is also observed that among the peoples who later appeared on the historical stage, the Medes left the fewest written sources. Therefore, information about this period is quite limited, and this gap can largely be filled through archaeological data.

Source: Wikipedia

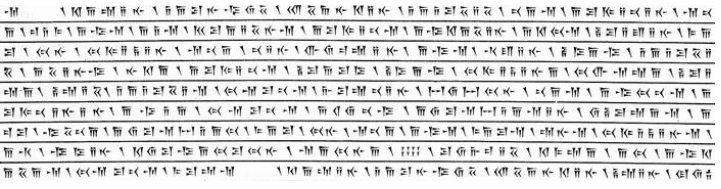

The Iranians established their first world empire with the Achaemenids (550–330 BCE). During the Achaemenid period, the name “Armenian” appears for the first time in the Behistun Inscription.

Source: Livius

The image above is related to the Behistun Inscription, and the first statements concerning the Armenians appear in this inscription. Darius states the following regarding the Armenians: King Darius says: “I sent an Armenian named Dâdarši, my servant, to Armenia and I told him: ‘Go and defeat that army which is in rebellion and does not acknowledge me.’” With these words, Darius sent an Armenian named Dâdarši to suppress the rebellion. Later, in the inscriptions above, he states that Ahura Mazda helped him, and thanks to this assistance he was able to crush the revolt. To read the Behistun Inscription, you may refer to the following website:

(https://www.livius.org/sources/content/behistun-persian-text/behistun-t-01/)

In history, Armenians first appeared on the stage in this manner through the Persians, and they achieved this by serving the Persians.

Throughout history, Armenians have almost never truly known what freedom is. Their geography has functioned both as a buffer zone and as a region frequently subjected to invasions. For this reason, Armenians were unable to establish a strong political structure. In this regard, they display similarities with the Jews. They also share common features with the Jews in terms of a strong sense of attachment to land. Both peoples possess narratives of exile. Although land became even more valuable after the rise of nationalist movements, among Jews and Armenians, land-based identity has continued to exist much more strongly. Religion has also had a significant impact on this situation.

The Achaemenids could no longer resist the attacks of Alexander of Macedon. Armenians also fought alongside the Achaemenids against the Macedonians during this period. While the Achaemenids were defeated, Armenians later declared their independence. During this era, Hellenistic culture became dominant. Later, during the Arsacid (Parthian) period, Iranians and Armenians lived together for approximately 400 years. Armenians held a shared position in governance during this time. While they could not go beyond being a puppet of the Romans, the Arsacid kings provided Armenians with a broader political sphere, and Arsacid culture became quite widespread among Armenians in this period.

As a good example of linguistic similarity, we may consider the suffix -yan. In Armenian, the suffix -yan means “son.” Armanyan means “son of Arman.” In Persian, names also sometimes take the suffix -yan; Pezeşkiyan is a good example. Although these words do not carry exactly the same meaning, they share similarities because both languages belong to the Indo-European language family. In the ancient period, there were significant similarities between Armenian and Persian.

Armenians have gone down in history as the first community to adopt Christianity. They became Christian in 301 AD. After this date, for many centuries, clergymen played a significant role in Armenia’s foreign policy and cultural life. In fact, the founders of the Armenian alphabet were also clergymen.

Since the Ottoman Empire applied the millet system, Armenian clergy gained considerable influence. Before adopting Christianity, Armenians followed a religion similar to Zoroastrianism. Zoroastrianism emerged during the Median period and became the official state religion during the Achaemenid era. In this period, Darius stated that he won wars with the help of Ahura Mazda. During the Sasanian period, however, a policy of religious uniformity was adopted, meaning that everyone was expected to become Zoroastrian. This led to increasing pressure on communities such as the Armenians, who had separated from Zoroastrianism. During the reign of Yazdegerd II, particularly severe oppression was imposed on Armenians. As a result of these religious pressures, the relatively small Arab forces were able to advance rapidly among the dissatisfied population and carry out their conquests. With the Arab conquests, the Sasanians withdrew from the stage of history; however, their administrative and cultural traditions continued to survive. Even today, there are still Zoroastrians living in the world.

During the Sasanian era, Armenians also remained in the buffer zone between Byzantium and the Sasanian Empire and suffered oppression as they were trapped between the two powers. Their geography historically imposed upon them the role of being a buffer region. During the Ottoman period, Armenians similarly assumed a buffer role between the Ottoman and Iranian powers. In this process, Shah Abbas deported Armenians into the interior of Iran. Sources also mention that a considerable number of Armenians lost their lives during this deportation.

The longest period of Armenian independence occurred after the collapse of the Sasanians. From that point onward, Armenians lived independently for approximately 200 years. Generally speaking, Armenians lived about 1000 years in freedom and about 1000 years under foreign domination. This situation led them to develop not a continuous state tradition, but rather a continuous “historical consciousness.” Such cultural characteristics enabled Armenians to survive throughout history.

The meaning of the name Zoroaster is “the owner of a yellow camel.” It can also mean “bright star,” “camel driver,” and “golden-colored light.” In those periods, the camel was a symbol of social status and was considered one of the most strategic animals for survival. People who owned camels were listened to more and held greater authority. Moreover, Zoroastrianism emerged in regions such as Iran, where a significant part of the land consists of deserts. The image above belongs to Persepolis, which Iranians call Takht-e Jamshid, and the Achaemenids held their celebrations there. Camel figures are frequently seen in the engravings carved into the walls of this site. From this, it is clearly understood how important the camel was.

Iran was unable to establish political unity during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. In later centuries as well, a stable environment did not exist for Iranians. During the reign of Shah Ismail, Iran began to become Shi‘ite and re-emerged on the stage of history as a state. The power formed around Shah Ismail, his charismatic aura, and his undefeated record in wars quickly brought him great success. During these periods, Armenians took part among the forces located in border regions and were able to participate in the Ottoman–Iranian wars. Additionally, some Armenian writers recorded the history of these periods.

During the reign of Shah Abbas, Armenians were moved from the western regions of Iran to Isfahan. The silk trade was entrusted to them, and through this they gained great wealth. Later, similar to what was often done to Jews in the West, they lost their former wealthy status during the reign of Nader Shah due to heavy taxation. Today, throughout the Islamic period, Armenia has become one of the neighbors with whom Iran has had the best relations, and Armenians have been among the happiest religious and ethnic minorities in Iran.

From the period of Karim Khan Zand onward, Armenians gradually began to regain their former position. Iran’s first Minister of Industry was also an Armenian: Cengizhan. A significant part of the intellectual foundation behind the establishment of industry in Iran also came from Armenians. Armenians first learned industrial practices from Russia, and later acquired knowledge about industry from the West. When Armenia declared its independence in 1991, Iran was among the first countries to recognize this independence. Armenians also established the printing press in Iran. Throughout history, two nations stand out for developing trade wherever they went: Armenians and Jews. Armenians played a decisive role in Iran’s trade between Europe and Russia. They also made significant contributions in the fields of cinema and photography, and provided notable services in medicine as well.

During the Soviet Union period, Iran did not have a serious relationship with Armenians. Iran perceived both Russia and Turkey as threats. In regional polarizations, Iran supported the Western bloc. For this reason, it did not develop a significant relationship with Armenians. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Iran was compelled to re-approach Russia. Armenia declared its independence but remained outside direct Russian protection. Due to wars with Azerbaijan, it needed a reliable ally. When Turkey and Azerbaijan closed their borders, landlocked Armenia’s connection with the world was largely cut off. In this situation, Iran became almost a lifeline for Armenia.

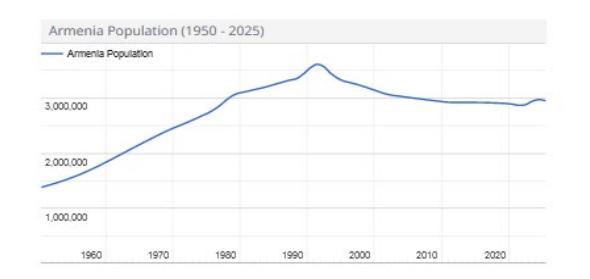

The image shows that the post-Soviet economy deteriorated rapidly.

During the Soviet period, Armenia was in a strong position in terms of industry, employment, education, and healthcare. It was part of the Soviet system; the population was increasing, and the unemployment rate remained low. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia entered a period of widespread corruption. Despite the fact that nearly 93% of its population was ethnically homogeneous, the country experienced large-scale migration. In this process, a diaspora emerged, and since the emigrants largely consisted of educated segments of society, Armenians gradually gained a powerful lobbying influence over time. By also making use of the “genocide” narrative, they gained significant momentum in the international arena. Iran, in turn, was able to benefit from this Armenian lobbying power and thereby partially break its international isolation.

“The Caucasus serves as a gateway of interaction among three major religions—Islam, Christianity, and Judaism—as well as among Turkish, Russian, and Iranian cultures, and more than fifty ethnic and linguistic groups live in this region.”

Approximately 120,000 Armenians live in Iran. There are around 200 Armenian churches in Iran, about 40 of which are currently active. Armenians also have their own schools and educational system. In 1992, Iran and Armenia mutually opened embassies. Armenian President Levon Ter-Petrosyan visited Iran three times, Serzh Sargsyan once, and Robert Kocharyan once.

One of the biggest issues between Iran and Armenia has been the Karabakh conflict. Since this issue directly concerns Azerbaijan, it occasionally causes problems. Iran’s cooperation with Armenia, in particular, has led to tensions between Iran and the Islamic world. Moreover, by improving its relations with Armenia, Iran aims to limit the influence of Turkey and NATO in the region. The presence of a large Azerbaijani Turk population in Iran also constitutes a separate source of concern for Iran.

Iranians view Armenia as “an ancient Aryan memory.” In ancient times, both societies were significantly influenced by Indo-European civilization. In bilateral relations, Armenia exports meat, paper, steel, mechanical and medical equipment, coffee, and mineral water to Iran. Iran, on the other hand, exports natural gas, petroleum products, household goods, fertilizer, glass, fruits, and vegetables to Armenia.

One of the areas of cooperation between Iran and Armenia has also been religion. Armenians are granted the right to practice their religion with great freedom. Since very ancient times, Armenians have built churches in Iran. The oldest church in Iran is the St. Thaddeus Church, shown below. It is also known as the Black Church. This church has been included in UNESCO’s World Heritage List and is protected in this way.

There are also important churches in Julfa. One of the most significant churches there is the Vank Cathedral. Armenians carry out various cultural activities in this church. These cultural activities also have a connection with Turkey. A map referred to as the “genocide map” is displayed there. In order to introduce this map, it was considered necessary to conduct such a comprehensive study. In order to understand the background of the map, it is first necessary to comprehend Iran’s relationship with Armenia.

New Julfa Church

Accepting the so-called “genocide map” does not seem very possible. During the Ottoman period, a mutual massacre—in other words, a reciprocal conflict (mukatele)—took place between Armenians and Muslims. Communities began to harm their neighbors with whom they had lived together, also under the pressure of foreign powers. Since the period was a time of war, it is not possible to claim that the actions carried out were one hundred percent justified; however, there is hardly any nation in history that has never experienced exile. Turks were expelled from the Balkans, Muslims from Andalusia, Ahiska Turks from Central Asia, and Jews from many places they lived. For every nation, especially in the era of nation-states, the concepts of land and homeland carry great importance.

Nevertheless, Armenians were also deported by Iran, yet this issue is not brought to the agenda. Iran deported Armenians into the interior of the country, particularly to the Isfahan region. This event is called the “Great Deportation,” and during this deportation a considerable number of Armenians lost their lives. Despite this, neither Armenians nor Iran bring this matter into discussion. This shows that even sufferings are selectively emphasized, and some are systematically highlighted. Since Armenians have historically lived in buffer zones, they have almost become a nation for whom deportation has been inevitable. It is argued that the Ottoman State did not pursue a deliberate policy in this process. Similarly, during the Sasanian period, Armenians were also caught between Rome and the Sasanian Empire.

In an image taken from inside the Vank Cathedral, the coming of the Messiah—that is, the Second Coming of Jesus Christ—is depicted. In the upper part of the image, Jesus is portrayed in the position of a judge, seated together with his apostles. In the middle section, the scene of the dead rising from their graves is illustrated. In the lower section, depictions of hell can be seen. In this way, the lives of prophets and various religious narratives are portrayed inside the Vank Cathedral.

In Armenia, however, there is only one mosque. The name of this mosque is Masjid-e Kabud, meaning the Blue Mosque. Today, Persian language education is provided in this mosque by Iranians. During the Soviet period, when religious buildings were being closed, Yeghishe Charents, one of the greatest Armenian poets of the era, saved this mosque from destruction. Together with several other intellectuals, he ensured the preservation of this architecturally rich structure, such as the Blue Mosque. Yeghishe Charents is regarded as one of Armenia’s most important poets, and Ahmad Shamlu translated one of his poems into Persian.

The Blue Mosque is also used as a cultural center. Free Persian language courses are offered there. After Tajikistan, Armenia is among the places where Persian is taught most intensively in the world—particularly among CIS countries. Persian is taught in ten schools and in many universities. Armenian studies in Iranology are highly developed. Persian proverbs, the Qur’an, Qabusnameh, and the works of Rudaki, Rumi, and Hafez have been translated into Armenian.

After the invention of the Armenian alphabet, in the 5th century AD, distinguished works from other languages began to be translated into Armenian. The students of Mesrop Mashtots, the inventor of the alphabet, learned the widely spoken languages of their time, and in this context, they also learned Pahlavi. Likewise, in the 5th century, Movses Khorenatsi, regarded as the father of Armenian historiography, wrote his most important work, History of Armenia. In this work, he made various references to Iranian mythology. During the reign of Yazdegerd II, a war occurred between Iran and Armenia, and during this war, the خطاب (address/speech) of the Iranian commander was translated into Armenian.

Persian literature left a significant mark on Armenian literature. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Armenian poet Yerzngatsi advised his readers to recite his poems in the meter of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. The poems of Omar Khayyam were read within Armenian society. The tradition of poetry also held great importance in Armenia. Gods and heroes were glorified, and this understanding continued in a similar way in Iran as well. Armenians adopted much of their religious terminology through Persian. While translating the fundamental texts of Christianity, many Persian words were used. Today, Mehrdad Momeni, who studied in Armenia, personally funded the construction of a statue of Omar Khayyam and donated it to Armenia. Sayat Nova, one of the important figures of Armenian literature and music, was in Shiraz in the service of Karim Khan Zand. In the field of music as well, Armenians greatly influenced Iranian culture.

There has been a historical interaction between Armenians and Iranians spanning thousands of years. In Iranian academia, these relations are consistently portrayed within a positive framework. Although interest in these issues is relatively limited in Turkey, the peoples living in the Caucasus region are more closely concerned with such matters. In Azerbaijan, studies on the Caucasus region are highly developed. This makes it necessary to follow academic production in Azerbaijan. Since the language is also relatively understandable, we recommend the works of Azerbaijani Turks to those who are interested in the region. In this context, some distinguished researchers have been conducting studies in this field for some time.

Due to our geographical position, the Caucasus is among the regions that Turkey considers of secondary importance. Iran also gives secondary importance to this region. Russia stands out as the most influential power and main actor in the region. However, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, fifteen independent states emerged. These states may pursue different policies from one another. In recent years, the South Caucasus region has been shifting toward the axis of the United States, NATO, and Turkey. I hope that these developments will be beneficial and auspicious for Turkey.

References

Asatryan, G. S. (2002). Armenia and security issues in the South Caucasus. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, 1(3), 21–30.

Azizi, H., & Isachenko, D. (2023). Turkey–Iran rivalry in the changing geopolitics of the South Caucasus (SWP Comment No. 49). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP).

Kelbizadeh, E. (2022). The main aspects and problems of Armenia–Iran energy diplomacy. Çankırı Karatekin University Journal of the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 37–51.

Kelkiltli, F. A. (2023). Soğuk Savaş sonrası Ermenistan–İran ilişkileri: Gelişen ve derinleşen bağlar [Armenian-Iranian relations after the Cold War: Improving and deepening bonds]. [Yayın bilgisi belirtilmemiş].

Koolaee, E., & Taghiabad, S. M. H. (2019). Science diplomacy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in the South Caucasus. International Studies Journal, 15(4), 99–131.

Məmmədli, A. A. (2019). İran–Ermənistan mədəni əlaqələrinin əsas cəhətləri. Bakı Universitetinin Xəbərləri: Humanitar Elmlər Seriyası, (2).

Mojtahedzadeh, P., Hosseinpour Pouyan, R., & Karimi Pour, Y. (2019). Tahlīl va barrasī-ye hampeūshī-ye sīyāsat-e khārejī-ye Jomhūrī-ye Eslāmī-ye Īrān dar ta‘āmol bā Jomhūrī-ye Āzarbāyjān bā vāqe‘īyat-hā-ye zhūpālītīk

[Analysis of the foreign policy coherence of the Islamic Republic of Iran in relations with the Republic of Azerbaijan: Geopolitical realities]. Bakı Universitetinin Xəbərləri: Humanitar Elmlər Seriyası, (2), 45–66.

Nezāmabadi, M. (2016). Ravābet-e farhangī-ye Īrān va Armenestān: Zarfīyat-hā va potānsīl-hā

[Cultural relations between Iran and Armenia: Capacities and potentials]. Motāleʿāt-e Farhangī va Ertebātāt, 12(43), 65–87.

Roohi, M. (2023). An analysis of Iran–Armenia relations after the collapse of the Soviet Union: Convergence theory and the strategy of the Islamic Republic of Iran. New Geopolitics Research.

Ozan Dur

Yorum Yaz