İlim ve Medeniyet

Yeni Nesil Sosyal Bilimler Platformu

Relations Between Armenian and Persian

Language is the roadmap of a culture.

It reveals where the people of that culture come from and where they are heading.

Rita Mae Brown

Armenians and Iranians live in geographically very close regions. Since both belong to the Indo-European language family, they share a common linguistic ancestor. It is said that there is a similarity rate of between 30 and 50 percent between Armenian and Persian. Speakers of Armenian and Persian can identify common words in everyday language.

However, the relationship between Persian and Armenian and the major influence of Persian occurred during the Achaemenid, Sasanian, and Arsacid periods. Persian exhibits the characteristics of a dominant language. Dominant languages tend to give words to other languages and rarely borrow words from them. Today, English is a dominant language that provides vocabulary to almost all languages. Persian, on the other hand, was at one time a lingua franca, that is, a common language. Unlike English, it did not function as a global lingua franca but rather maintained its status as a regional common language. During these periods, it also succeeded in influencing other languages. It can be argued that Persian was perhaps the language that most strongly influenced Armenian in the classical period. Apart from this, Armenian was also influenced by Greek and borrowed words from it.

When European scholars first began to study Armenian in the nineteenth century, they identified a close relationship between Armenian and Persian. They considered Armenian to be so closely related to Persian that they described it as an “Iranian language.” It was viewed as a sub-branch of the Iranian languages. Heinrich Hübschmann (1848–1908) was the first scholar to argue that Armenian was not an Iranian language but rather had borrowed vocabulary from Persian, and to demonstrate this scientifically. However, even he was unable to use unequivocal statements in his book asserting that Armenian was an entirely separate language. He could not be fully certain, as the view that Armenian was an Iranian language was very widespread at the time. He expressed this situation with the following words: “Müller’s view that Armenian is an Iranian language has not been refuted and must, for the present, be regarded as the most solidly established and dominant view.”

Farrokh (Faruk) states that Hübschmann’s greatest achievement was not focusing on words themselves, but rather on their phonological correspondences. For example, when a sound (letter) in one language corresponds to a sound (letter) in another language, this is referred to as a “phonological correspondence.” In Proto-Indo-European, ped means “foot,” and the letter “p” is preserved in Latin. In Latin, pes also means “foot,” whereas in English the letter “p” changes into “f,” resulting in foot. Thus, the “p” sound in Proto-Indo-European corresponds to the “f” sound in English. Hübschmann drew attention to such changes and demonstrated that Armenian was not an Iranian language.

In Hebrew, for example, the letter “y” corresponds to the letter “v” in Arabic. Yeled means “child” in Hebrew, while veled means “child” in Arabic. Similar sound changes, such as b–v, are also quite common. Paying attention to such correspondences is crucial for identifying the genetic relationships of languages.

Historically, Armenians did not have their own alphabet. They used the alphabets of different peoples. In the pre-nationalist period, languages were not regarded as components of a nation. Linguistic purity was not sought, and the use of foreign words was not considered shameful.

Armenian rulers minted coins bearing Greek inscriptions. During the reign of the Armenian king Tigranes II (96–56 BCE), Greek was the language of the court. Armenians were influenced by high culture, and the prestigious lifestyle of the Greeks must have had an impact on them. Armenians even used among themselves the names of Sasanian and Arsacid rulers, because the Arsacids represented a high culture and Armenians sought to emulate them.

The portrait above belongs to Artavasdes II, and the following inscription appears in Greek:

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΑΡΤΑΥΑΖΔΟΥ ΘΕΟΥ

Basileōs basileōn Artavazdou theou

“Artavasdes, King of Kings, the son of God”

Persian rulers also used the title Shahanshah, meaning “King of Kings.” In the prehistorical period, Armenians were strongly influenced by Hellenic culture. In later periods, Persians and the Persian language influenced Armenians. Armenians were the first community in history to adopt Christianity. Their religious literature was transmitted through Greek. They incorporated religious literature into their language via Greek, and Greek words entered Armenian as a result.

In the Armenian Bible, Persian words can also be found. This is because knowledge of the abstract realm had initially been accessed through Persian. Persian religious literature entered both Armenian and, in later periods, Turkish. This may have been influenced by the fact that Armenians possessed a strong Zoroastrian tradition, which was one of the most widespread belief systems of its time.

As an example of such words, the Armenian term ašakert, meaning “student” or “disciple,” may be cited. Its Iranian origin is hašagird. Although it is used today as şakirt, the word is of Persian origin and was later Arabized. Its meaning is “a person who is being trained.” After the Islamic period, the word danişcu entered Persian, meaning “one who seeks knowledge.” [In my opinion, it would be better to render the word “student” as “one who seeks wisdom.”]

Another Armenian word is hreštak, meaning “angel.” In earlier periods it appeared as freštag, while in the modern period the “g” was dropped, resulting in firişte.

This period most likely belonged to a time prior to Hellenic influence, because Armenians were significantly influenced by the Achaemenids. Before adopting Christianity, they also shared the same religion as Iran. They were influenced by Iranian deities. One of the Old Persian divine names, Aurumazdâ, appeared in Armenian as Aramazd. Mihr was likewise Mihr, the Sun God. There were also strong similarities in place names. The word ostan denoted a place name, and Armenia is called Hayastan in Armenian. While Hay means Armenian, the suffix -astan derives from the word ostan. Names such as Pakistan and Turkmenistan are also connected to the Armenian word ostan.

Several additional regional names can be examined in tabular form:

|

Suffix |

Function |

Armenian Examples |

Source / Notes |

|

–astan |

Place names, countries |

asp-astan “horse stable”; dar-astan “garden”; hay-astan “Armenia”; huž-astan “Susiana”; Asorestan “Syria” |

Ir. -stāna-; Parth., Mid. Pers. stān |

|

–aran |

Place names, locations |

ganj-aran “treasury”; zoh-aran “sacrificial altar”; Bag-aran (place name) |

Ir. dāna- “container, place”; Parth. –’ān; O. Pers. daivadāna- |

|

–arên |

Language names, adjectives |

yown-arên “Greek”; asorarên “Syriac” |

Ir. -ādayana- “manner, way”; Parth. āδēn; N. Pers. āyīn |

|

–kar |

“one who does, makes” |

awgt-a-kar “profitable”; vnas-a-kar “harmful” |

Ir. -kara-/-kāra; Parth., Mid. Pers. –gar/-gār |

During the Arsacid period (1st century BCE – 4th century CE), many Persian-origin words entered Armenian. The form of Persian used during this period was Parthian. While words related to daily life entered Armenian during this era, administrative, military, and governmental terms entered the language during the Sasanian period. Parthian is classified as a Northwestern Iranian language, whereas Pahlavi (Middle Persian) is regarded as a Southwestern dialect.

It is said that the first Persian word to enter Armenian was Ari-k. The suffix -k carries the meaning of pluralization (“-s”), thus referring to Arians, that is, Aryans. Persian words later passed into Georgian through Armenian, although they did not leave as strong an impact as they did in Armenian. It is said that 25 percent of Armenian personal names are of Iranian origin. Many names in Turkish also ultimately derive from Persian, such as Dilara, Suzan, Dilber, and Feridun.

Armenians converted to Christianity in the third century, and after this date they strongly preserved their Christian identity. During the periods of Seljuk, Ottoman, and Safavid rule, relatively few words from the languages of these states entered Armenian. Christianity enabled the preservation of a strong collective identity. Prior to Christianity, Persian had exerted the principal influence on the Armenian language.

Until the fourth century CE, Armenians did not have their own alphabet. In 405, Mesrop Mashtots, together with his students, created a national alphabet. In the process of developing this alphabet, Mashtots examined Syriac, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin. Together with his students, he established the alphabet of the Armenian language as it is known today. The alphabet consists of 36 letters.

Busts of Mashtots have been erected in various regions of Armenia. Armenians are deeply attached to their language and their religion.

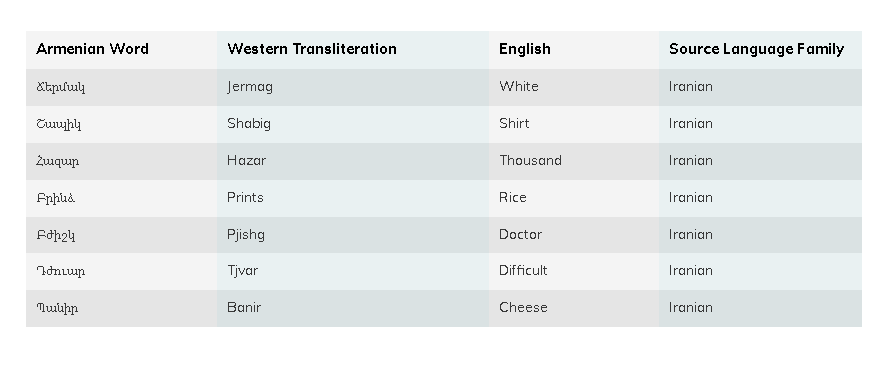

Let us take a look at the words that entered Armenian from Parthian and Pahlavi.

|

Armenian |

Meaning |

Source Language |

Notes |

|

ašteay |

spear |

Parth. aršti-; ṛšti-, Av. aršti- |

— |

|

aspar |

shield |

Parth., Middle Persian ispar |

Defensive tool |

|

awar |

booty, spoils |

Parth. āwār |

Post-war |

|

gownd |

unit, troops |

Parth., Middle Persian gund |

Military organization |

Armenian military terminology entered the language through Parthian and Pahlavi. Words such as spear, shield, helmet, and dagger were borrowed from these languages.

|

Armenian |

Meaning |

Source Language |

Notes |

|

ahōr |

stable |

Parth., Middle Persian āxwarr |

New Persian āhor |

|

aspastan |

horse stable |

Middle Persian aspastān |

Av. aspo-stāna- |

|

asp-a-rês |

horse race, hippodrome |

Calque (loan translation) |

Middle Persian asp-rēs |

|

aspet |

knight, cavalryman |

Parth., Middle Persian asppat |

Derived from aspapet |

|

smb-ak |

hoof |

Middle Persian sumb |

New Persian sonb, Arabic sonbak |

Words related to stables, horses, and equestrian life were also borrowed from Persian.

|

Armenian |

Meaning |

Source Language |

Notes |

|

ahok |

crime, fault |

Middle Persian āhōg |

New Persian āhū |

|

apastan |

refuge, shelter |

Middle Persian abestān |

Security |

|

arāt |

abundant, rich, generous |

Parth., Middle Persian rād |

Social value |

|

dep-kʿ |

accident, event |

Parth., Middle Persian dēb |

Meaning “fate, fortune” |

|

džowar |

difficult, hard |

Middle Persian dušwār |

New Persian došvār |

|

dsrov |

accused |

Middle Persian dusraw |

Social judgment |

|

zowr |

empty, useless, false |

Parth., Middle Persian zūr |

Worthlessness |

|

žaman-ak |

time, era |

Parth. žamān; Middle Persian zamān(ag) |

Chronology |

|

Armenian |

Meaning |

Source Language |

Notes |

|

anowšak |

immortal |

Parth., Middle Persian anōšag |

Spiritual concept |

|

ašakert |

student, disciple |

Middle Persian hašāgird |

New Persian šāgerd |

|

awrhnem |

to bless, praise, offer |

Parth., Middle Persian āfrīn- |

Religious act |

|

bag– |

god (in proper names) |

Parth. baγ; Middle Persian bay |

Divine name |

|

baht |

fate, fortune |

Middle Persian baxt |

Av. baxta- |

|

den |

religion, faith |

Parth., Middle Persian dēn |

Zoroastrian term |

Approximately 2,500 root words in Armenian originate from Persian and Greek. During the Ottoman period, Ottoman Turkish words entered the Armenian language. At the same time, movements toward linguistic purification emerged. Armenians who used foreign words were shamed and socially stigmatized. Although this movement is largely regarded as successful, many words in Classical Armenian were also borrowed from other languages. The notion of absolute linguistic purification proved to be a myth.

Classical Armenian was presented as the model of “pure” or “eloquent” Armenian, yet this form of Armenian also contained numerous Persian and Greek words. Therefore, it is not possible to speak of absolute purification. Today, Classical Armenian is used in liturgical services in churches in Armenia; however, it is said that a significant portion of the population does not understand it.

Moreover, written and spoken Armenian are treated as distinct forms of the language. There are also thinkers who express concern that this situation may produce adverse effects.

Turkish word in Armenian

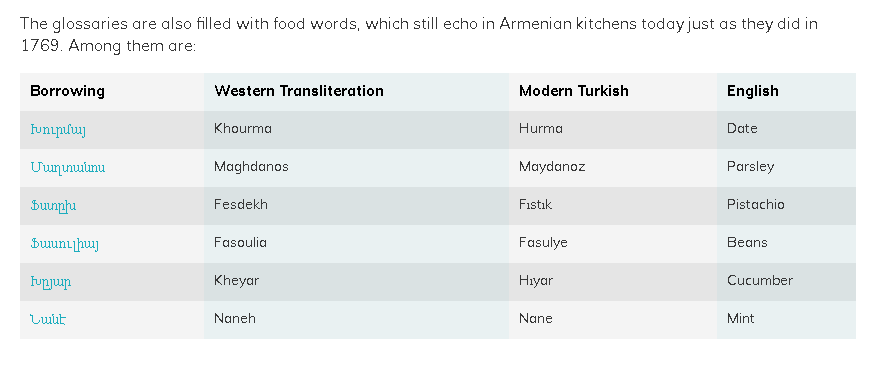

The Armenian culinary tradition has also been virtually overtaken by Turkish words.

Armenians recite the following rhyme at an early age in schools. I am sharing both the Armenian text and its meaning.

Աշ-խար-հա-բառ խօ-սած ա-տե-նըս պէտք չէ՛ որ խօս-քիս մէ-ջը այ-լազ-գա-կան բա-ռեր խառ-նեմ, որ-պէս զի խօ-սած լե-զուս խառ-նած չըլլայ՝ հա-պա՝ մա-քուր ըլլայ։ Թէ որ բա-ռի մը աշ-խար-հա-բառը չեմ գի-տեր՝ պէտք է որ վար-պե-տիս հար-ցը-նեմ ու սոր-վիմ, որ աղէկ խօ-սիմ։

“While speaking, I should not mix foreign words into my speech so that the language I speak does not become corrupted and remains pure. If I do not know the correct word for something, I should ask my teacher and learn it, so that I may speak properly.”

In this way, Armenians are encouraged from an early age to avoid using foreign words. Although children receive this type of education, it should not be assumed that Armenians living abroad undergo a similar process of linguistic training, and this situation brings with it certain difficulties, such as avoiding speaking the language altogether.

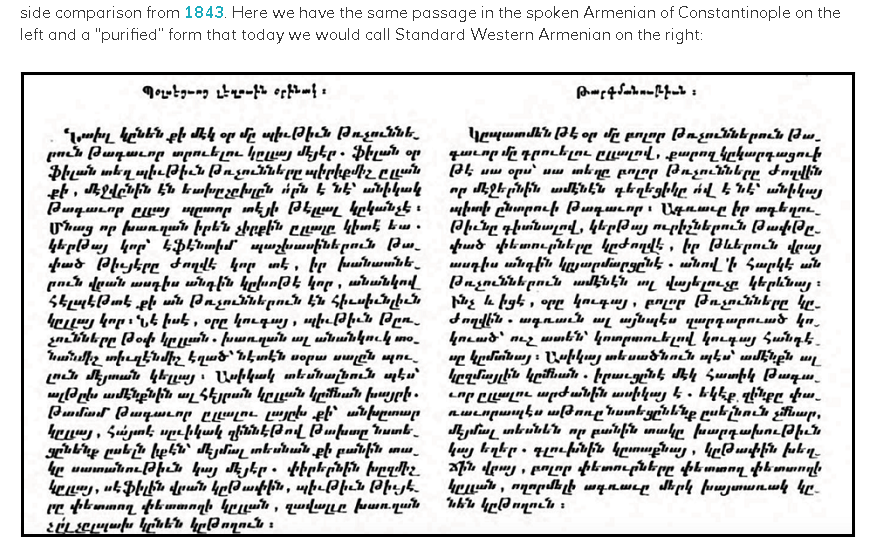

On the left is Eastern Armenian, that is, the written form of Armenian spoken in Turkey, while on the right there is a purified form of Armenian. The written language of Western Armenian was purified and cleansed of Ottoman Turkish from the nineteenth century onward. In spoken language, however, the use of Turkish words continued. Armenians living in Istanbul used a significantly higher number of Turkish words. According to one estimate, 4,200 Turkish loanwords were in use.

The author makes the following ironic observation:

“However, there is an ironic point in this nineteenth-century campaign for linguistic purity and in the efforts of today’s purists: many of the Classical Armenian words praised as ‘pure’ were once borrowings themselves. Achieving purity is always merely an ideal, a myth, an impossibility in regions of the world where cultural contact is constant. Classical Armenian could not escape this contact; on the contrary, it was constructed by it. A large part of its vocabulary, down to its most basic words, was borrowed from other languages in the region. The continuous recourse to Classical Armenian in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in order to replace loanwords meant that many of these historical borrowings entered Standard Western Armenian and continue to exist today as the building blocks of the language.”

As stated, it is not possible to remove all foreign words from a language, and this endeavor is nothing more than a myth. The author also reacts critically to this situation. Pre-nationalist Armenians engaged in far less nationalism with regard to the Armenian language—indeed, much less—since there were even poets who composed poetry using words from multiple languages. Such linguistic sensitivity had not yet developed.

As we have noted, a large number of Persian words entered Armenian during the classical period. A significant portion of the words mentioned above are still used in Modern Persian, although their number is not very large. It is stated that 30–40 percent of Armenian is derived from Classical Persian. When Armenians and Iranians spoke with one another, they were able to identify certain shared words.

Within the Indo-European language family, there exists a body of vocabulary that has passed into many different languages. Armenians are also considered to be part of the Indo-European civilizational sphere. For example, the Persian berâder, the English brother, and the German Bruder all derive from the same root. When the West sought to conquer India, it discovered Sanskrit and acknowledged it as the language of a great civilization. One of the major civilizational basins of the past was the Indian civilization.

|

Proto–Indo-European |

Meaning (EN) |

Armenian (Grabar / Modern) |

|

pətēr |

father |

հայր hayr |

|

mātēr |

mother |

մայր mayr |

|

sunús |

son |

որդի vordi |

|

dhughater |

daughter |

դուստր dustr |

|

bhrātor / bhrater |

brother |

եղբայր yeğbayr / yeghpayr |

In this study, we have attempted to address the relationship between Armenian and Persian. As seen in names such as Iran and Yerevan, there are many similarities between Persian and Armenian words. Armenians and Iranians, whose relations have fluctuated throughout history, today maintain relatively better relations. When non-Christian states are examined, Iran is seen to be the country where the greatest number of churches have been built. A significant portion of these churches remain active. While there is one mosque in Armenia, there are dozens of active churches in Iran.

There is a district inhabited by Armenians in Julfa. In the Vank Church, Armenians have even created a “genocide” map. Today, Armenians have attained a respected position in Iran. Iran’s first minister of industry was an Armenian named Cengizhan. The prosperity they achieved during the reign of Shah Abbas has, in many ways, been attained again today. The relationships of the classical period have, in a sense, been revived in the present day.

References

Farrokh, K. (n.d.). Position of Armenian within the scope of Indo-European languages. Kaveh Farrokh – Iranian Studies.

https://www.kavehfarrokh.com/iranian-studies/iranica/iran-caucasia/position-of-armenian-within-the-scope-of-indo-european-languages/

Stepanyan, E. (2022). A survey on loanwords and borrowings and their role in the reflection of cultural values and democracy development: The Armenian paradigm. European Journal of Marketing and Economics, 5(2), 108.

Kettenhofen, E., & Schmitt, R. (2014). Hübschmann, (Johann) Heinrich. Encyclopædia Iranica. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/hbschmann-johann-heinrich/

İlim ve Medeniyet. (2021, 15 Eylül). Ermeni alfabesinin dil, din ve kimlik üçgeninde Tanrı’dan İsa’ya yolculuğu. İlim ve Medeniyet. https://www.ilimvemedeniyet.com/ermeni-alfabesinin-dil-din-ve-kimlik-ucgeninde-tanridan-isaya-yolculugu

Hübschmann, H. (1895–1897). Armenische Grammatik. Breitkopf & Härtel. (Eserin dijital kopyası: https://archive.org/details/ArmenischeGrammatik

Schmitt, R., & Bailey, H. W. (1986). Armenia and Iran iv. Iranian influences in Armenian language. In Encyclopædia Iranica (Vol. II, Fasc. 4-5, pp. 445–465). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/armenia-iv/

Manoukian, J. (2022, August 5). That’s not Armenian! Encounters with language purists past and present. H-Pem. https://www.h-pem.com/en/submissions/2022/08/05/thats-not-armenian-encounters-with-language-purists-past-and-present/54

Ač‘aryan, H. (1940). Hayots lezvi patmut‘yun, I mas [History of the Armenian language, Vol. 1]. Yerevan State University Press. (Eserin dijital baskısı: https://archive.org/details/lezvip1)

Ozan Dur (Turkiye based Middle East and language researcher)

Yorum Yaz