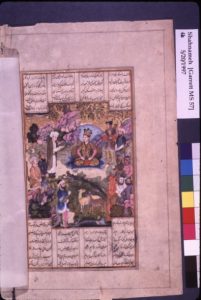

“Kıyumers is giving his son the training that will enable him to defeat the giants.”

İlim ve Medeniyet

Yeni Nesil Sosyal Bilimler Platformu

THE SHĀHNĀME OF FIRDAWSĪ AND ITS DIFFUSION IN ANATOLIA

This article examines the stages of writing the Shāhnāmeh and its dissemination in the Anatolian geography. It focuses on Abū al-Qāsim Firdawsī, who was born in 940, the composition of his work, his presentation of the Shāhnāmeh to Sultan Maḥmūd of Ghazna, the sources he used during its composition, and the subsequent spread of the work in Anatolia. Moreover, after the work was completed, it first reached the Seljuks and later, successively, the Karamanids and the Ottomans. The chronological development of this process is analyzed in this article.

Keywords: Firdawsī, Ottomans, Anatolia, Shāhnāmeh, Dissemination

Firdawsī was born in the village of Bāz in the district of Ṭāberān, belonging to the city of Ṭūs (Hüseyni Dešti, 23). There are various accounts regarding his name, but it has not been possible to determine which is correct (Kanar, 1996, p. 125-127). Similarly, while there are many conflicting reports regarding his birth, it is generally accepted that he was born in 940 (Lugal, 2005, p. 15).

To understand Firdawsī’s work, it is necessary to consider the conditions he lived in, his life, his thought, and his feelings. He lived during the Samanid period. With the Samanids, the declining Persian language began to revive. In addition, the Samanid state was in decline and under the pressure of Arabs and Turks (Ritter, 1889, p. 643-645). In such an environment, Firdawsī was born into a dehqān family (Sefa, 1354).

Being born a dehqān implied certain responsibilities and a worldview. Dehqāns of that period considered themselves heirs to Iranian national values and culture (Lugal, 2005, p. 15-16). Accordingly, Firdawsī received education aligned with this perspective and studied history, primarily Iranian history, until the age of 25 (Lugal, 2005, p. 16-17). He learned Pahlavi from the Zoroastrian priests of his era and his father. It is known that he mastered Arabic and Persian very well (Kanar, 1996, p. 125-127). Moreover, he had access to primary sources and had helpers who assisted him.

Firdawsī was not the first to write a Shāhnāmeh. Several Shāhnāmehs had been written before him. While composing his work, he benefited from many existing Shāhnāmehs and similar sources. What distinguished Firdawsī from others was making a little-known Shāhnāmeh writing tradition famous and widely recognized (Gültekin, 2013, p. 239-261). After his work, many Shāhnāmehs were written, and his work was translated into numerous world languages, bringing the art of Shāhnāmeh writing to a new level.

Before starting to write, Firdawsī had to ensure that someone would support him during the composition. To obtain such support, he needed to prove his competence. Indeed, he had proven it; he had written poetry before the Shāhnāmeh (Lugal, 2005, p. 17), and his proficiency in languages was sufficient to gain a patron.

As mentioned, he did not write the Shāhnāmeh first. Being born a dehqān, he had a developed dehqān culture, and early on, written and oral sources related to Iranian history were collected under the Samanids (Lugal, 2005, p. 23-24). Later, during the Sasanian period, the first Shāhnāmeh was written, known in sources as Khudāynāmeh. Firdawsī would later benefit extensively from this work (Lugal, 2005, p. 23-24). He also drew on texts such as the Avesta, the Torah, the Qur’an, and the works of previous Shāhnāmeh writers. Based on these sources, he began writing around 980 or 990, completed the first redaction in 1004, and the final redaction in 1018 (Kanar, 2010, p. 289-290; Lugal, 2005, p. 24).

Firdawsī aimed to present an ideal world to Iranians. He wanted to demonstrate the grandeur of their past, encourage them to be powerful and glorious, revive Iranian culture and values, enhance patriotism, maintain the connection with ancient Iran, awaken the people, and instill independence (Lugal, 2005, p. 24-25).

It took him approximately 30 to 35 years to complete the work. During this time, those who helped him either died or withdrew their assistance. He also mentions severe winters causing the loss of his possessions. Consequently, he sought to sell the work for profit. Encouraged by his friends, he presented it to Ghaznavid Sultan Maḥmūd. However, when he did not receive the expected recognition, sources mention that he composed satirical works and left (Ritter, 1889, p. 645; Lugal, 2005, p. 21).

Among those who helped him was his wife, noted for her artistic and musical skills (Lugal, 2005, p. 21).

The initial reaction to the completed work is not clearly recorded, but it seems that shortly after completion, its fame spread rapidly. One indication is that, according to a tradition, Sultan Maḥmūd sent gifts to Firdawsī after realizing his mistake, which reflects the swift recognition of the work (Ritter, 1889, p. 645). Secondly, the first known translation was made by the Ayyubid historian Bundārī in the 12th century (Kanar, 2010, p. 289-290), indicating the work gained fame relatively quickly.

After completion and recognition, the work began to spread. Its significance is related to why it spread. As mentioned, Firdawsī wrote the Shāhnāmeh with certain objectives, which it exceeded. The importance of the work stems from presenting “ideal heroes,” utilizing sacred texts (Torah, Qur’an, Avesta), composing in a manner suitable for multiple sects (Muhammed Nuri Osmanov, 1971), providing practical guidance for daily life (Woodhead, 2010, p. 456), and insisting on Iranian independence without interfering with the lands of others.

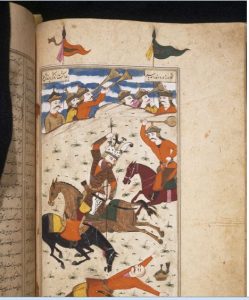

Rüstem is fighting with the Turks

Later, the work spread to Anatolia via the Seljuks. Information about its translation is scarce, but a Shāhnāmeh writing tradition emerged under the Seljuks. In the first half of the 13th century, Amīn Aḥmad Kanīʾī wrote a Shāhnāmeh on the order of ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Kayqubād I. When the Karamanids emerged, claiming to be the heirs of the Seljuks, Shāhnāmeh writing became significant. The first Karamanid Shāhnāmeh was written in 1313 by a Khurasani named Ünsī, followed by writers like Yarjānī and Dehhānī (Çiftçioğlu, 58-59).

The Seljuks embraced Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmeh so fully that some of their princes’ names were identical to the heroes of Firdawsī (Muhammedi, 449). The Ottoman Empire inherited this tradition. The first translation into Turkish was commissioned by Murad II, followed by Sharīf-ī Āmidī under Qānṣūh al-Ghawrī, completed in 1511 for Yavuz Sultan Selim. The third translation was by Derviş Hasan under Osman II (Kültüral, 2010, p. 290-292).

Subsequently, semi-official court historiography and Shāhnāmeh writing emerged, particularly after the conquest of Istanbul. Iranian poets were brought to the court and salaried. Works such as Muʿālī’s Persian Khunkārnāmeh and Kāshifī’s Ghāzānāmeh-i Rūm survive, while others like Hamīdī and Shehdī are lost (Özcan, 2007, p. 274; Woodhead, 2010, p. 456-458).

Later, Shāhnāmeh writing transitioned from semi-official to official historiography. Officials were called şehnāmecī, also şehname-gū or şehname-nūvīs. The office was institutionalized under Suleiman the Magnificent in 1550 to narrate the state’s contemporary history in literary style. It lasted until 1601, during which five official şehnāmecīs were appointed (Woodhead, 2010, p. 456-458).

From the tenure of Lokmān onwards, Persian lost its dominance; prose replaced verse, and Turkish gradually replaced Persian. Sultan Mehmed III reportedly instructed his şehnāmecī to write in Turkish (Woodhead, 2010, p. 456-458).

While many articles exist on the topic, some merely repeat previous sources without exploring different perspectives. Researchers often rely on existing debates rather than examining the work from new angles.

It is essential that this globally important work undergo more extensive research and investigation.

Çağman, F., İnalcık, H., & Renda, G. (2003). Osmanlı uygarlığı [Ottoman civilization]. Ankara: Yapı Kredi Yayınları.

Çiftçioğlu, İ. (n.d.). Karamanlı dönemi Şehname yazarları ve eserleri [Shāhnāmeh writers and works during the Karamanid period]. Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 58–59.

Gültekin, H. (2013). Şeh-nâme, Şeh-nâmecilik ve meşâhîr-‘i İslâm’da Fîrdevsî maddesi [The Shāhnāmeh, Shāhnāmeh writing, and Firdawsī in Islamic luminaries]. International Journal of Social Science, 6(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/xxxxx

Hüseyni Dešti, S. M. (n.d.). Firdevsî [Firdawsī]. Me’arif ve Me’ârîf, 7, 23.

Kanar, M. (1996). Firdevsî [Firdawsī]. DİA, 13, 125–127.

Kanar, M. (2010). Şehname [Shāhnāmeh]. DİA, 38, 289–292.

Kültüral, Z. (2010). Şahname [Shāhnāmeh]. DİA, 38, 290–292.

Lugal, N. (2005). Şāhnāmeh Firdawsī [Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmeh]. İstanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi Yayınları.

Muhammedi. (n.d.). Edebi Farisi der Anadolu ve Balkan [Persian literature in Anatolia and the Balkans]. Danişnâme-yi edebi Farisi, 6, 449.

Osmanov, M. N. (1971). Metn-i İntikadi ve İlmi-yi Şahname-i Firdawsî [Critical and scholarly text of Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmeh]. Tehran: [Publisher].

Özcan, A. (2007). Osmanlı tarihçiliğine ve tarih kaynaklarına genel bir bakış [An overview of Ottoman historiography and historical sources]. FSM İlmî Araştırmalar İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Dergisi, 1, 274.

Ritter, H. (1889). Firdevsî-Şehnâme [Firdawsī–Shāhnāmeh]. İslam Ansiklopedisi, 4, 643–645.

Sefa, Z. (1354). Berresiha-yi der bare-yi Şāhnāmeh-yi Firdawsî [Study on Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmeh]. Tehran: [Publisher].

Woodhead, C. (2010). Şehnāmeci [Shāhnāmeh writer]. DİA, 38, 456–458.

Ozan Dur

Türkiye Based Middle East Researcher

Translated by ia

Yorum Yaz