İlim ve Medeniyet

Yeni Nesil Sosyal Bilimler Platformu

Khomeini and the Iranian Islamic Revolution – With Photographs of the Era

Khomeini was born in 1901 in the village of Humeym near Qom. It is said that his lineage reaches back to the Prophet, meaning he was considered a sayyid. His ancestors first migrated from Nishapur to India and later settled in Najaf, Iran (Algar, 1993). Khomeini lost his father at a very early age and was raised by his mother and aunt. After their deaths, he continued his scholarly life under the guardianship of his elder brother. It is said that the hardships he experienced during this period had a significant impact on his life. His mother died of cholera in 1918 (Axworthy, 2016). His father was killed when he was only five months old, though different accounts exist regarding the circumstances of his death (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

At the age of seven, Khomeini began his traditional education. His brother served as his teacher for a time and later continued to support him in his scholarly pursuits. Khomeini studied in Isfahan, Arak, and Najaf before moving to Qom in 1922 to further his education. In Qom, he not only studied jurisprudence but also developed an interest in philosophy and other sciences. During his time there, he attended lectures by prominent scholars and also taught the public (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

Within 15–16 years, Khomeini demonstrated the potential to become a marjaʿ al-taqlid (source of emulation). Taflıoğlu notes that this was a remarkably short period. Continuing his studies, Khomeini married at the age of 27, the same year he authored Misbah al-Hidaya (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

His presence in Qom marked a turning point in his life. It is said that since 1930 he had been in contact with those opposing the Pahlavi regime (Algar, 1993). Although he did not actively engage in politics until the 1940s, one of his most significant achievements was introducing politics into Qom. Previously, those who attempted to do so had been expelled and discredited (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

Ahmad Kasravi wrote The Thousand-Year Mysteries (Asrar-e Hezar Sal), to which Khomeini responded with Kashf al-Asrar (The Unveiling of Secrets). In this work, he explained the theory of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist). The book is also significant for its political content. Taflıoğlu finds it remarkable that Khomeini, who had criticized those involved in politics for neglecting prayer, authored a politically charged work. He further notes that in this book, written nearly 38 years before the revolution, Khomeini already spoke of an “Islamic Order” (Taflıoğlu, 2009). This suggests that long before the revolution, Khomeini had a vision for the system he wished to establish. Thus, it would be inaccurate to claim that when he returned from France during the revolution, he had no idea about how the state should be governed.

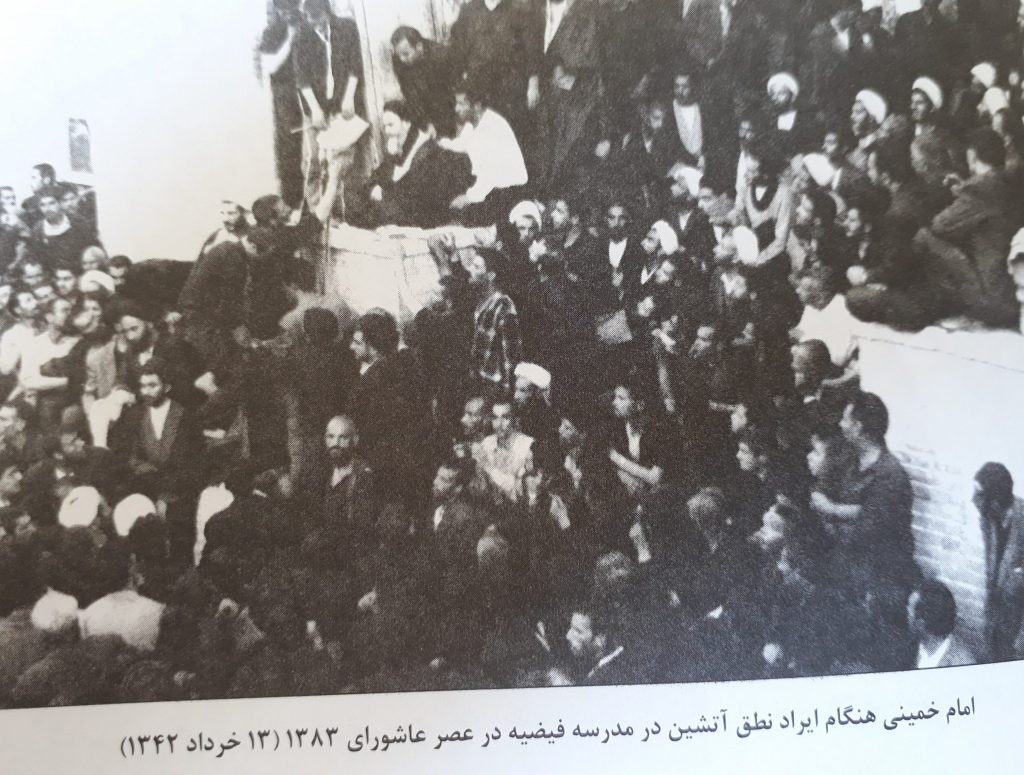

Khomeini’s authority and reputation began with the death of Ayatollah Borujerdi in 1961, after which Khomeini was chosen as a marjaʿ al-taqlid (Algar, 2004). In 1962, two significant developments occurred. First, Khomeini prevented the proposal to abolish the oath on the Qur’an in municipal elections. Second, the Shah announced his reform program known as the “White Revolution.” Khomeini sent a letter demanding its cancellation, which the Shah rejected. In 1963, Khomeini issued a declaration protesting the Shah. Tensions escalated, leading to numerous uprisings until 1979, many of which resulted in deaths. As the Shah intensified repression, Khomeini’s rhetoric grew stronger. In 1963, the Shah’s forces attacked the Fayziyeh Seminary, killing and arresting students. On the 40th day after the incident, Khomeini delivered a speech that led to his arrest. These events became known in Iranian history as the 15 Khordad Uprising (Algar, 1993).

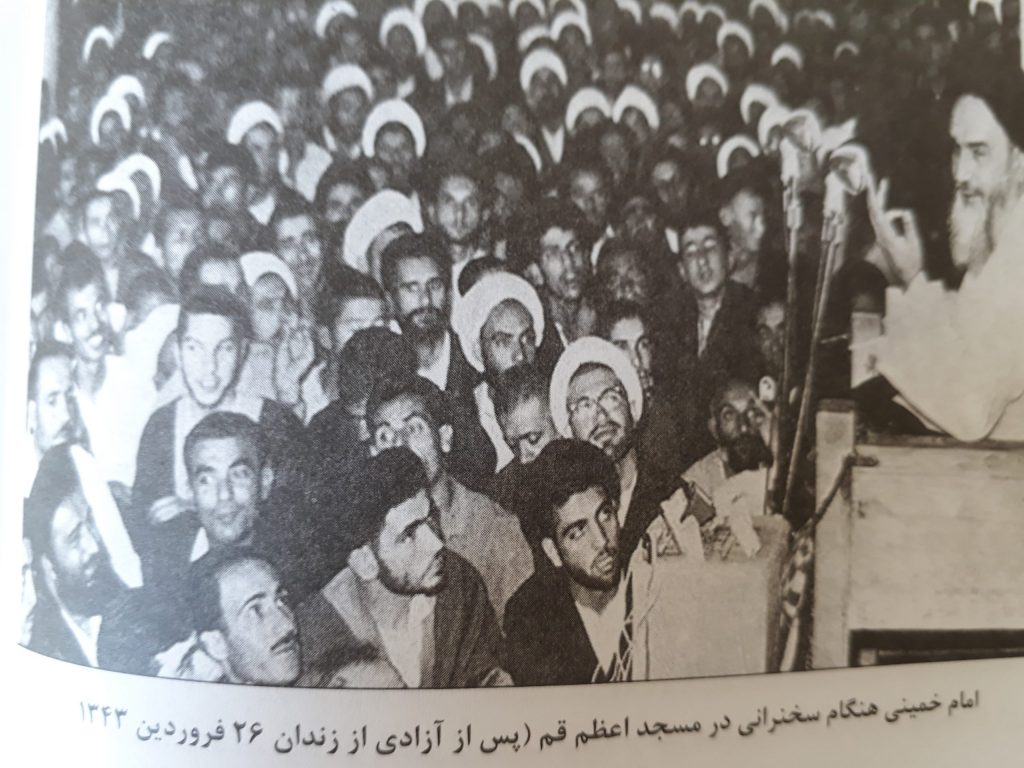

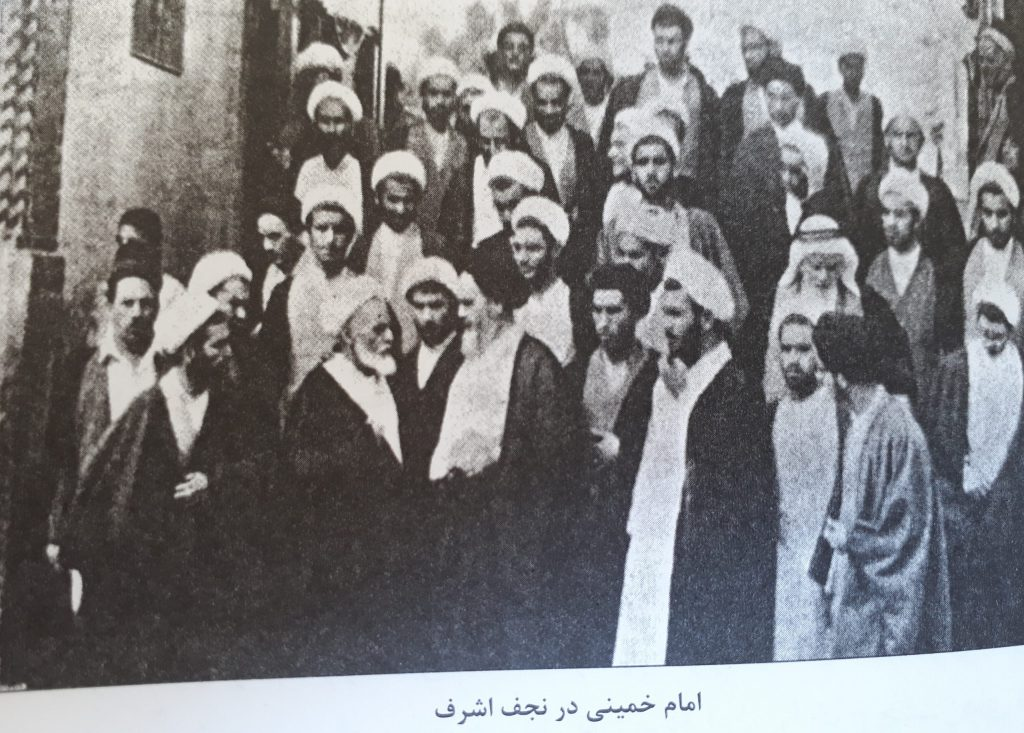

Demonstrations spread across the country, and Khomeini was released on April 7, 1964. Later that year, when a law was passed granting Americans immunity from Iranian courts, Khomeini denounced those responsible as traitors and delivered a significant speech. Shortly afterward, he was exiled. Following brief stays in Ankara and Bursa, he moved to Najaf, where he remained for about 13 years (Algar, 1993).

During his time in Najaf, particularly from 1970 onward, Khomeini delivered lectures on Velayat-e Faqih. This concept marked a major shift in Shiʿi thought. Traditionally, Shiʿis believed that governance belonged solely to the Imams, specifically the hidden Twelfth Imam. In this context, rulers were considered usurpers. Khomeini, however, argued that Shiʿi jurists should assume leadership during the occultation. Although the term Velayat-e Faqih had long existed, it became a political theory in the 19th century. Previously, jurists held authority in matters such as marriage and divorce but refrained from political governance, considering it an infringement on the Imam’s rights (Taflıoğlu, 2009; Üstün, 2013). Khomeini expanded their authority, asserting that jurists should govern during the period of occultation.

His lectures in Najaf were smuggled into Iran. From 1970 onward, some of these sermons were published under the title Islamic Government, presenting a comprehensive account of Velayat-e Faqih (Garthwaite, 2011).

In 1971, Iran celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of its monarchy with a grand ceremony attended by many foreign dignitaries. Enormous sums were spent on the event. From Iraq, Khomeini criticized the monarchy. The adoption of Cyrus’s coronation day as a substitute for the Islamic calendar alarmed scholars and distanced them from the regime (Axworthy, 2016). During the ceremony, the Shah declared:

“O Cyrus, Great King, King of Kings, Achaemenid King, King of the land of Iran! I, the Shahanshah of Iran, bring you greetings from myself and my nation. At this exalted moment in Iran’s history, we, the children of the empire you founded 2,500 years ago, bow before your tomb with respect. With your immortal memory and the glorious past of the new Iran rekindled, our hearts are filled with enthusiasm…” (Garthwaite, 2011).

In 1975, the Resurrection Party (Hezb-e Rastakhiz) was founded. Its establishment and policies provoked public resentment. That year’s inflation further alienated the bazaars. As a result of government measures, 250,000 people were penalized. In an unprecedented move, the bazaars sought refuge with the clergy (Abrahamian, 2014). Subsequently, clerics issued fatwas against the party, and Khomeini himself condemned it. Many scholars were arrested (Abrahamian, 2014). These events deeply affected Iranian society.

Khomeini in 1978 and His Departure from Najaf

In 1978, Khomeini was forced to leave Najaf, where he had been living for many years. During his time there, his name was associated with several important events. In the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, when he advocated for the boycott of Israeli goods, his house was looted. In 1965, members of the Heyʿathā-ye Hizb-e Motalefeh organization, which included some of Khomeini’s students, carried out an assassination against Prime Minister Hasan Ali Mansur, who had exiled Khomeini. In 1977, Khomeini’s son was killed, and it was claimed that SAVAK was responsible. In 1978, when a semi-official newspaper published an article labeling Khomeini a traitor, the public erupted in anger, and the uprising was brutally suppressed. Later, in Abadan, approximately 410 people died when the doors of a cinema were locked and set ablaze (Algar, 1993).

Although martial law was declared afterward, public hatred toward the Shah had reached its peak. In 1978, Khomeini’s house was besieged, and upon his son’s advice, he went to France. Although he stated that he did not wish to live in a non-Muslim country and preferred a Muslim country where freedom of expression was respected, no Muslim country granted him permission, so he remained in France (Algar, 1993).

Khomeini’s Political Struggle and the Iranian Islamic Revolution

Taflıoğlu divides Khomeini’s political struggle into three phases. According to him, the first phase spans from 1940 to 1960, during which Khomeini did not actively participate in politics but expressed his views in his lectures. The second phase begins with his becoming a marjaʿ al-taqlid in 1962 and continues until the Iranian Islamic Revolution in 1979, during which he was actively engaged in politics. The final phase encompasses the period after the revolution (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

There were numerous reasons behind the occurrence of the Iranian Islamic Revolution and the unification of the people in anti-Shah and anti-monarchy rhetoric. The Shah sought to implement reforms, build a strong Iran, and elevate the country to the level of contemporary civilizations in many fields. However, these reforms caused unrest among the social base upon which the Pahlavi regime relied. It is said that his initiatives ultimately failed. While the number of schools, students, and Iranians studying abroad increased, Abrahamian notes that these reforms did not yield the desired results and that the first wave of brain drain was associated with Iran.

Abrahamian explains the revolution as follows:

“The cause of the revolution was not some last-minute political mistake. It was the eruption of decades of accumulated pressures within Iranian society, like a volcano. By 1977, the Shah, alienated from nearly every sector of society, was sitting atop such a volcano. By stubbornly opposing intellectuals and the urban working class, he prepared his own downfall. This opposition intensified over the years. In the age of republicanism, the Shah flaunted monarchy, kingship, and Pahlavism. In the age of nationalism and anti-imperialism, his rise to power was the direct result of the CIA-MI6 collaboration that overthrew Mossadegh, the symbol of Iranian nationalism. In the age of neutrality, he mocked the Non-Aligned Movement and Third Worldism, instead dedicating himself to being America’s policeman in the Persian Gulf, openly siding with the United States on sensitive issues such as Palestine and Vietnam. In the age of democracy, the Shah exalted the virtues of order, discipline, guidance, kingship, and personal communication with God” (Abrahamian, 2014).

Taflıoğlu, on the other hand, begins the conflict between the Shah and the clergy in 1959. Before this period, due to the rise of communism in the country, the clergy regarded the Shah almost as a savior. They demanded that the Shah halt the activities of the Bahá’ís and protect Shiʿism. The building where the Bahá’ís gathered was demolished by the army itself. Yet this mutual tolerance would not last long. The Shah, once seen as the protector of Shiʿism, began to draw criticism for certain policies, and tensions with the clergy grew. The Shah’s reforms, particularly those known as the White Revolution, provoked strong reactions from the clergy. These laws included reforms such as granting women the right to vote, which the clergy considered forbidden and contrary to Islam. Although Borujerdi warned the Shah before his death, the Shah continued with these reforms, and other scholars also took a stance against him (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

The Road to the Islamic Revolution and the Fall of the Monarchy – The Grey Revolution

The event that widened the gap between the Shah and the clergy—perhaps irreversibly—was what I call the Grey Revolution. In Iranian history, this episode is known as the White Revolution, while Khomeini referred to it as the Black Revolution. I, however, describe it as the Grey Revolution. In 1962, the reforms the Shah sought to implement provoked strong reactions from the clergy. It appears that, while primarily focused on land reform, these reforms also contained provisions that the clergy opposed.

The most important element of the White Revolution was the land reform. Its aim was to break the power of large landowners. The clergy, however, believed that private property should be protected, and therefore opposed this reform (Garthwaite, 2011).

The Shah dissolved the parliament and decided to restructure it. Previously, members had sworn on the Qur’an, women did not have the right to vote or be elected, and non-Muslims were excluded. By attempting to change these rules, the Shah set himself against the clergy. In response, the clergy criticized the reforms and issued fatwas declaring them forbidden (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

The breaking point came in 1963, when Khomeini’s movement led to the cancellation of the Nowruz celebrations, which were declared a day of mourning due to the reforms. Following this, scholars were arrested, and the uprisings that ensued were violently suppressed, becoming known as the Bloody Khordad events (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

The Shah was determined to enforce his reforms harshly. Since the clergy stood against him, he sought measures to weaken their power. Seminaries were closed, and the number of students attending them was reduced. Laws were passed against their endowments. In place of seminaries, faculties of theology were established, and Persian culture was promoted over religion. The Shah claimed to be the “shadow of God on earth” and declared that he received divine assistance, which was seen as an attempt to undermine clerical authority. During this period, SAVAK was highly active. It is said that SAVAK paid salaries to 15,000 clerics, whom Khomeini criticized. Moreover, reports of SAVAK’s unofficial ties with Israel disturbed the clergy (Taflıoğlu, 2009).

The Shah’s policies provoked reactions among segments of society. The White Revolution and the subsequent establishment of the Resurrection Party were deeply unpopular among parts of the population. Some reforms both drew the clergy into politics and intensified their opposition to the Shah. When Jimmy Carter’s administration came to power, it emphasized human rights violations in Iran and other countries. The Shah, seeking to escape this pressure, made certain adjustments in government policies. In 1977, at a poetry recital, opposition writers read poems against the Shah, leading to clashes. Subsequently, confrontations occurred between the Shah’s soldiers and the participants, resulting in deaths and injuries (Abrahamian, 2014).

As noted earlier, in 1978 an article in Ettelaat newspaper denouncing Khomeini as a traitor sparked public outrage. On August 19, in Abadan, 400 women and children perished when a cinema was set ablaze with its doors locked. A crowd of 10,000 gathered, chanting “Down with the Pahlavis.” On September 8, events unfolded that became known as Black Friday. Soldiers under the Tehran governor opened fire on demonstrators who defied martial law and refused to disperse, effectively closing all paths of reconciliation between the Shah and the people (Abrahamian, 2014).

By then, the people openly declared their desire for an Islamic Republic, demanded Khomeini’s return, and rejected the Shah. On February 1, Khomeini returned from France. On February 11, weapons were seized from arsenals and distributed to the people. The regime’s end had arrived (Abrahamian, 2014). Abrahamian describes this period as follows:

“Two days of street fighting brought an end to a 53-year dynasty and a 2,500-year monarchy. One of the three pillars the Pahlavis had relied upon—the army—was paralyzed; the bureaucracy joined the revolution; and the palace patronage system was in utter disarray. The voice of the people had proven more powerful than the Pahlavi monarchy” (Abrahamian, 2014).

Among the causes of the Islamic Revolution, the economic crisis is also cited. Between 1963 and 1970, Iran’s economy grew rapidly. Yet this growth later turned into crisis, bringing new problems. Rising inflation forced the state to adopt harsh measures, which provoked public anger. The oil boom and the introduction of new agricultural techniques reduced the need for manual labor, leaving many unemployed. These people migrated to large cities, disrupting urban order and giving rise to a new social class (Axworthy, 2016).

In his work, Michael discusses the Iranian Revolution and the Pahlavi era, noting the number and influence of Americans living in Iran. He describes how Americans lived like kings, enjoying first-class privileges, even having their own hospitals. He also mentions occasional conflicts between young Iranians and Americans that reached the press (Axworthy, 2016).

Khomeini’s Role in the Revolution

The Iranian Islamic Revolution has been described by some as the greatest event in the Middle East after World War II. Consequently, in a region such as the Middle East—whose importance grew considerably in the 20th century—such a development has generated extensive commentary and scholarship. As a relatively recent historical event, we also possess visual materials such as photographs and videos that serve as historical sources. In this study, however, we have focused on the revolution through the lens of Khomeini’s life. In nearly all the works we examined, the years leading up to the revolution are narrated with reference to Khomeini. His prominence and his ability to influence broad segments of society on the path to revolution made possible the establishment of an Islamic state afterward. This outcome could not have been easily predicted long before the revolution. Once Khomeini became the focal point of anti-Shah rhetoric, the people began to rally around him and his views reached ever wider audiences.

There were, of course, other figures in society who thought differently from Khomeini and gained prominence. Ali Shariati, for instance, is said to have demanded a different kind of order than Khomeini envisioned. Other groups also existed, including those supported by Russia and other foreign powers. Nevertheless, it was Khomeini who ultimately assumed leadership of the country after the revolution.

Khomeini’s rise to prominence occurred especially after the 1960s. Several factors contributed to this. Most notably, following the death of Ayatollah Borujerdi in 1961, Khomeini gradually ascended to the position of marjaʿ al-taqlid. From that point onward, he increasingly became the focal point of opposition to the Shah. During this period, the clergy opposed the Shah’s land reforms, and those who resisted these reforms drew closer to the clerical establishment. After Khomeini’s exile, and particularly from 1970 onward, his lectures deeply influenced the public. His sermons were clandestinely smuggled into Iran. His emphasis on the concept of Velayat-e Faqih after 1970 was especially significant. Today, Velayat-e Faqih remains one of the fundamental doctrines of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Another turning point was the establishment of the Resurrection Party in 1975. With its creation, Iran entered a one-party era, and opposition parties were dissolved. Even the remaining opposition party’s degree of dissent was questionable. After the Resurrection Party was founded, bazaar merchants—blamed for inflation—were punished. It is said that approximately 250,000 people were penalized. Although the exact severity of these punishments is unclear, it is known that the policies of the Resurrection Party pushed the bazaar merchants into cooperation with the clergy. Thus, the Shah’s policies increasingly generated unrest among the population.

An important example of Khomeini’s popularity and influence in Iran occurred in 1978. That year, Ettelaat newspaper published accusations against him, branding him a traitor. In response, the people took to the streets to defend Khomeini. Their protests did not subside, and slogans demanding the Shah’s departure and Khomeini’s return were chanted. In the same year, the tragic Abadan cinema fire—where 400 women and children perished after the doors were locked—was blamed on the Shah. These events accelerated his downfall. By then, unrest was unstoppable. While Khomeini resided in France, his views continued to be reproduced and secretly circulated within Iran.

Assessing Khomeini’s precise role in the revolution, and making definitive conclusions, is not easy. The thesis that can be advanced here is that Khomeini’s success lay in his ability to stand out among other actors. He had prepared the groundwork with his ideas and teachings. In particular, through Velayat-e Faqih, the role and responsibilities of clerics in society were expanded. In short, clerics were to govern the state, or at least ensure that the state was administered in accordance with Islamic law through a supervisory mechanism. At the head of this mechanism had to be the most learned scholar, the mujtahid. Khomeini’s success lay precisely in his conviction that clerics should have a say in governance, and in persuading the people of this view. As a result, the revolution emerged as an Islamic revolution.

Had Khomeini not existed, or had Shariati or another figure taken his place, the outcome might have looked very different. Yet such counterfactuals hold little value. History unfolded as it did, and Khomeini’s success and influence derived from his ability to stand out far more than other actors, becoming the symbol of opposition to the Shah.

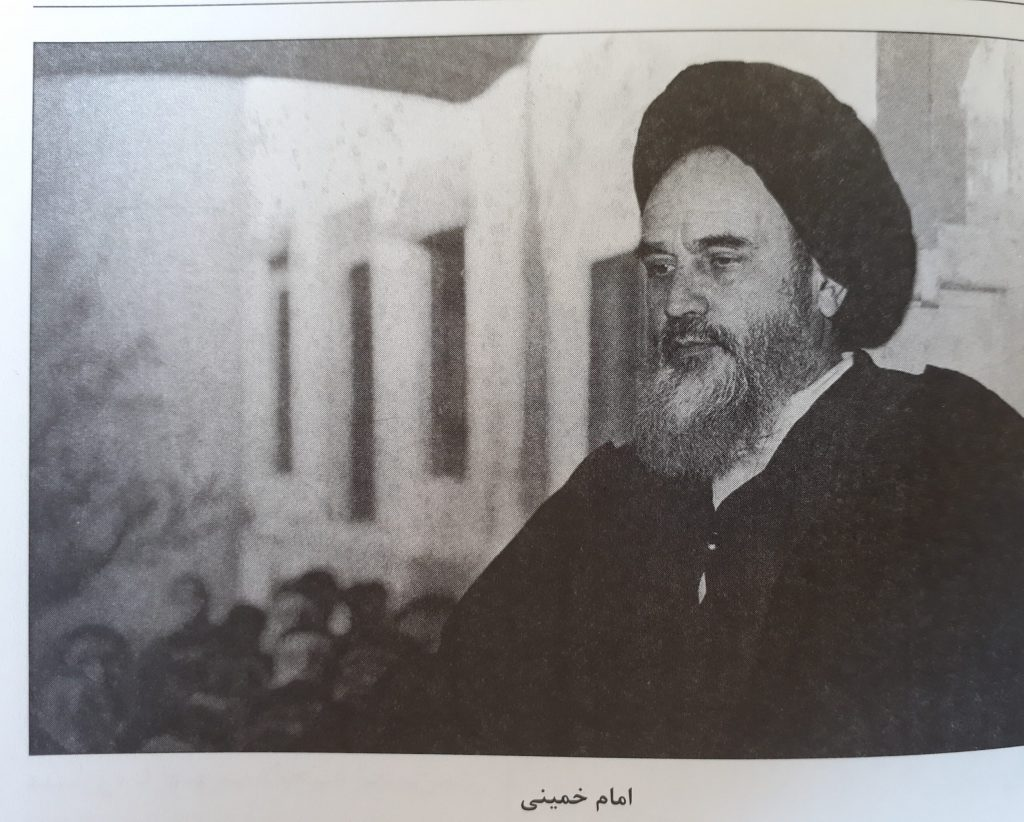

Imam Khomeini

Muhammad Reza Pahlavi’s Speech in Qom

“Imam Khomeini is delivering a lecture at the Fayziyeh Seminary.”

An image from Khomeini’s lecture in Qom

“An image of Khomeini during his time in Najaf.”

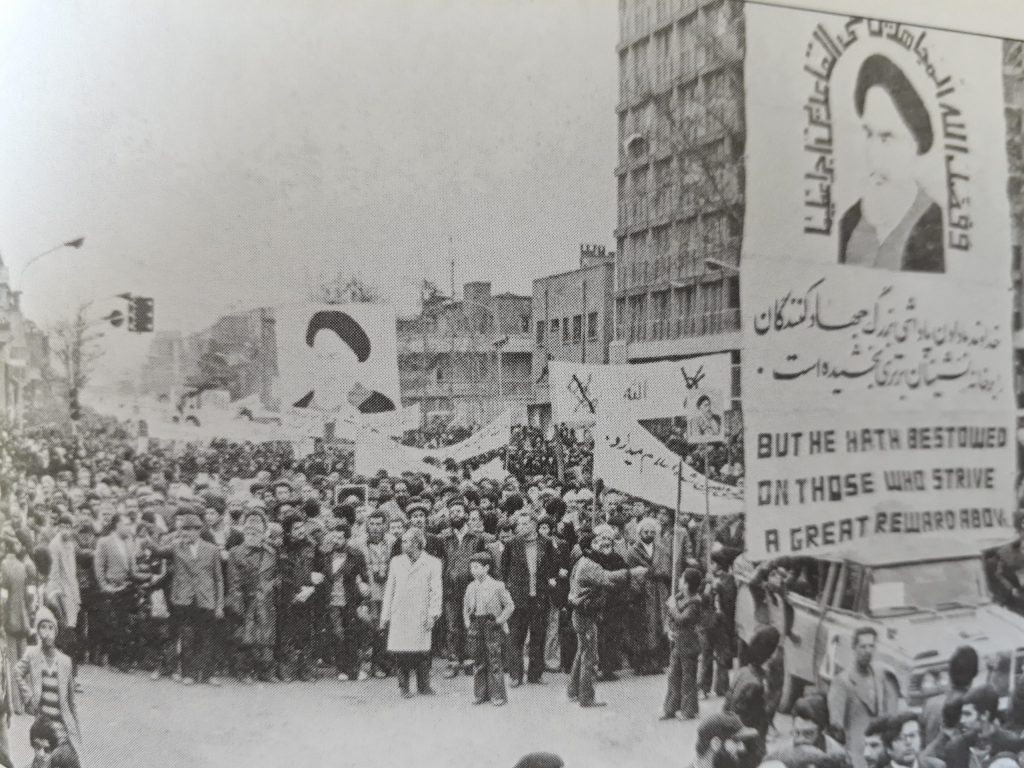

“The people are holding a demonstration in favor of Khomeini.”

“The confrontation between the people and the army.”

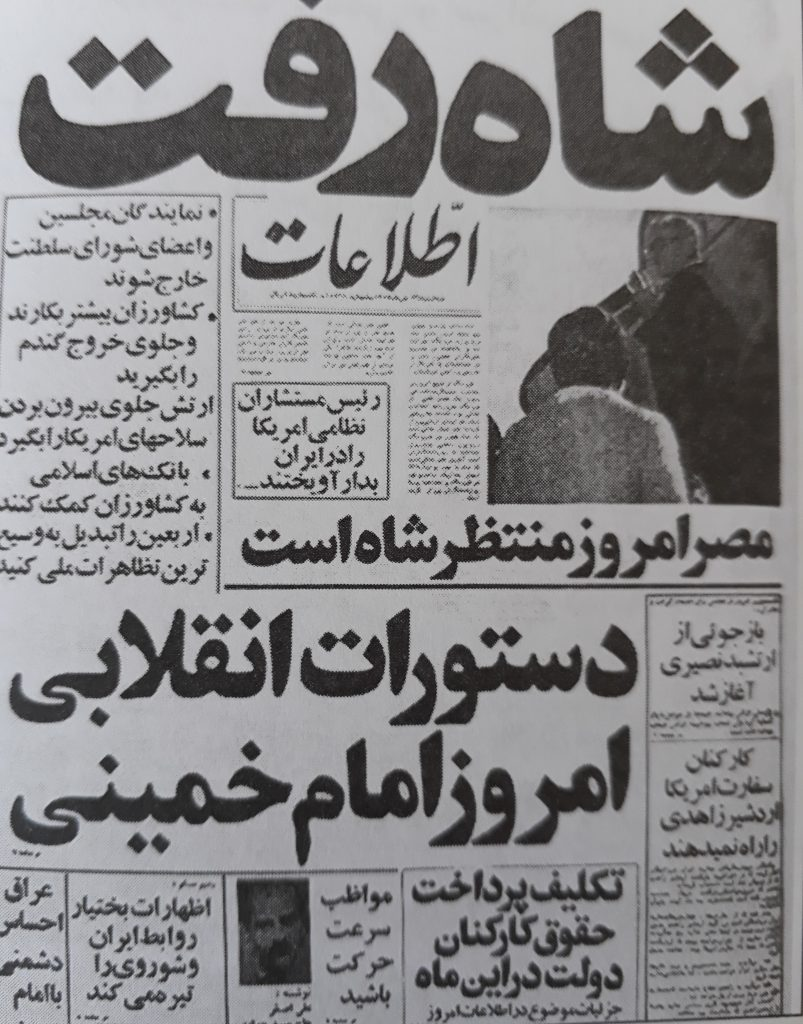

“The Ettelaat newspaper announces that the Shah has left.”

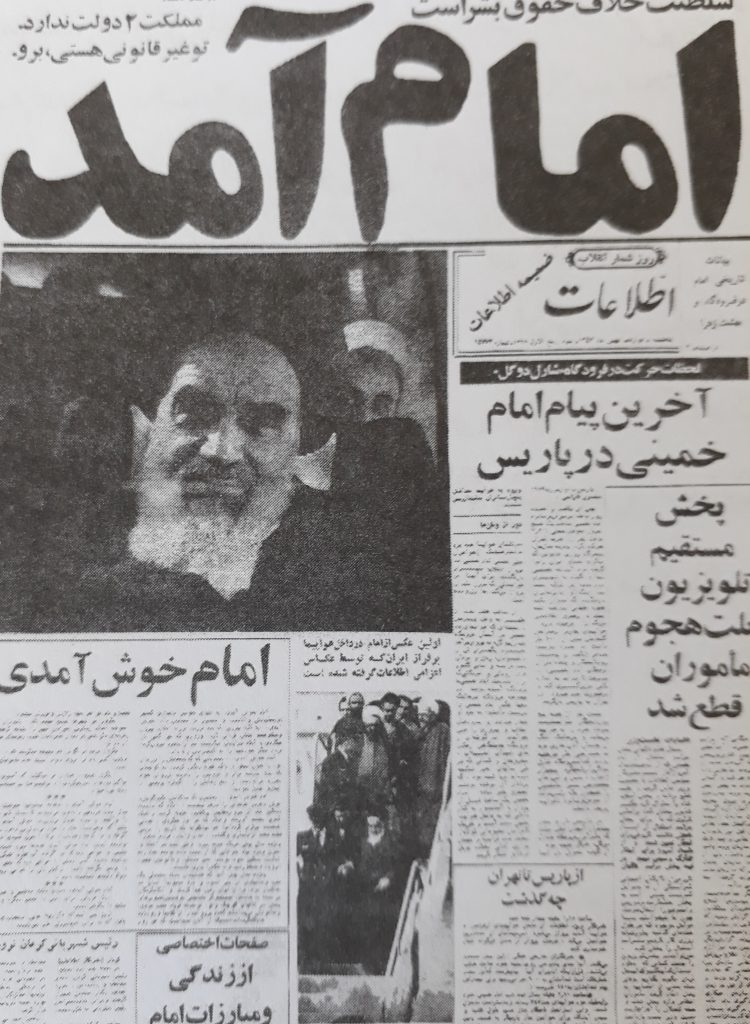

A shot showing Khomeini’s arrival

“The reflection of Khomeini’s arrival in the Ettelaat newspaper.”

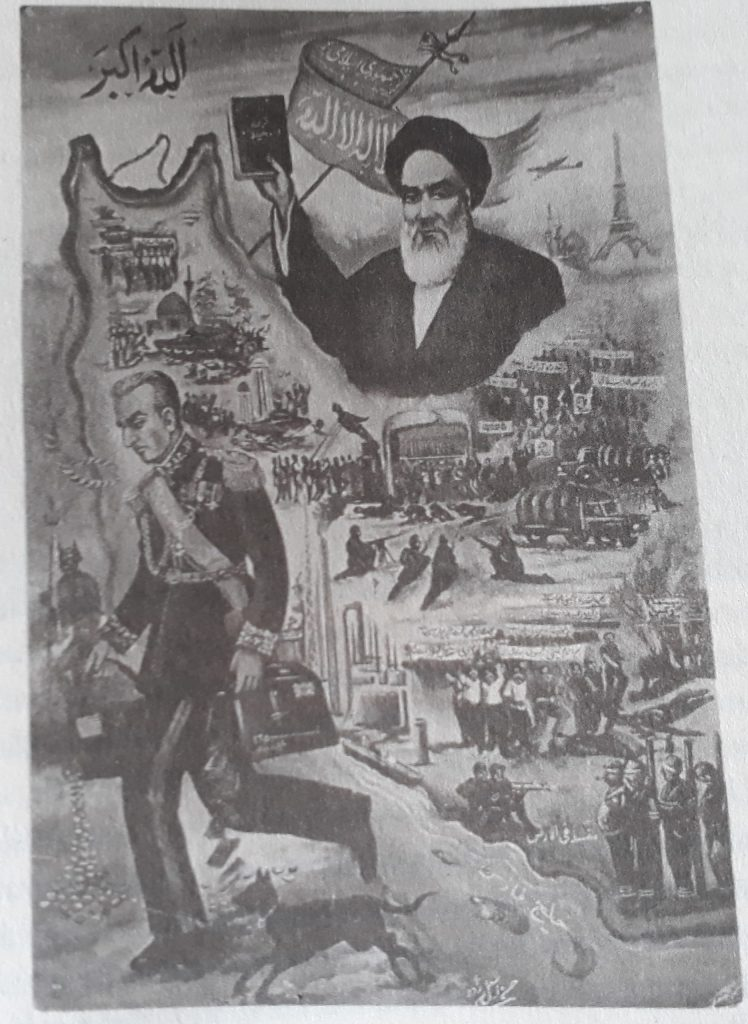

“A brochure showing the Shah’s departure and Khomeini’s return.”

“All of the above images are taken from the following book: Dr. Musa Necefi and Dr. Musa Faqih Hakkani, The History of Iran’s Political Transformations (Tehran: Institute for Contemporary Iranian Historical Studies, 2013)

References

Abrahamian, Ervand. Modern İran Tarihi. Çev. Dilek Şendil. İstanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası, 2014.

Algar, Hamid. “Humeyni.” DİA. 8. 358-364.

Axworthy, Michael. İran Aklın İmparatorluğu. Çev. Özlem Gitmez. İstanbul: Say, 2016.

Garthwaite, Gene R. İran Tarihi. Çev. Fethi Aytuna. İstanbul: İnkilap, 2011.

İzzeti, İzzetulah. İran ve Bölge Jeopolitiği. Çev. Hakkı Uygur. İstanbul: Küre, 2006.

Necefi, Doktor Musa ve Hakkani, Doktor Musa Fakih. Tarih-i Tehevvülat-ı Siyasi-i İran. Tahran: Müessese-i Mütalaat-ı Tarih-i Muasır-ı İran. 1392.

Safa üstün, İsmail. “Velayet-i Fakih.” DİA. 43. 19-22.

Taflıoğlu, Mehmet Serkan. “İran İslam İhtilalinde Ayetullah Humeyni ve Velayet-i Fakih Meselesi.” Doktora Tezi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi, 2009.

Ozan Dur

Türkiye based Middle East and History Researcher

Yorum Yaz